Trigger Warning: mentions of sexual assault

The objectification of women is quite similar to that of animals. In the same way animals are to humans, women are seen as second-class to men. This plays into the concept of speciesism.

Speciesism is the ideology of humans (including their rights, needs, wants, and interests) being above all other species of animal (Taylor et al, 2019).

Speciesism and sexism, in a lot of ways, are alike — and the meat industry has capitalised off this. Women are reduced to their body parts, while animals are reduced to the type of meat they produce; women are seen as entertainment by men, while animals are seen as performers at a circus; women are animalised, while animals are feminised and sexualised. Women are constantly being referred to as dogs, pigs, or chicks in order to reinforce the notion that women are below men. Doing this normalises the exploitation of women and animals, simultaneously.

“Women’s oppression is intensified by associating us with non-human animals.”

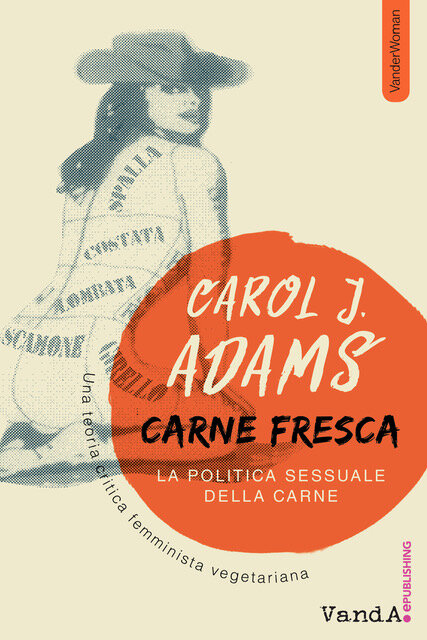

— Carol J. Adams

Side note: It must be acknowledged that this extends to people of colour and feeds into racism as well.

We often hear that animals are simply put on Earth for human consumption. In the meat and dairy industry, female animals are made to breed, and are later killed for meat. This is closely related to how women are treated in society — here to breed children and entertain men; and once they are too old and unbeautiful, they are no longer worth anything. This is best described by Carol J. Adams in her book ‘The Sexual Politics of Meat’, where she examines the patriarchal politics of our meat-eating culture and the link between speciesism and sexism.

Many of us know feminism advocates for women’s rights and liberation from the patriarchy. But, where does veganism come into play? Veganism assumes all animals (humans included) are at an even playing field; equal. Since minorities are compared to animals — i.e. women to chicks and dogs, black people to monkeys — anti-veganism is inherently perpetuating oppression. There is actually a specific movement called ‘vegetarian ecofeminism’ that aims to eradicate the oppression and harm humans inflict on non-human animals (Taylor et al, 2019). And doing so will stop the harm and insult of a human being compared to a non-human animal. Once an individual becomes vegan, they inherently begin fighting for this movement.

It’s been in media since the beginning of advertising; steak is for men. This concept of meat-eating perpetuating toxic masculinity feeds back into speciesism. “Men are above all other beings, so they deserve the best”. Not only is meat seen as a luxury food product in most parts of the world, it is associated with virility — these two combined create a true power only made for wealthy, white men. All while women are stuck with the salad, or other meals that only further promote diet culture.

This is because our culture masculinises meat-eating and feminises compassion.

There’s a prevalent stereotype in media surrounding vegans being crazy, radical, insane, mad… But who exactly is that stereotype referring to? Women are innately more compassionate, nurturing beings — which is why compassion is considered a feminine attribute. And to no surprise, 79% of vegans are women (Asher et al, 2014). Therefore, when society says “vegans are crazy”, we’re really just reinforcing the trope that women are crazy. Not to mention vegans (as we now know, for the most part, really just means ‘women’) are commonly depicted as weak or fragile.

TW: sexual assault

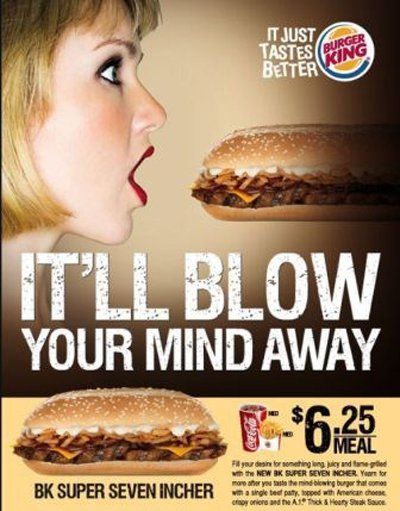

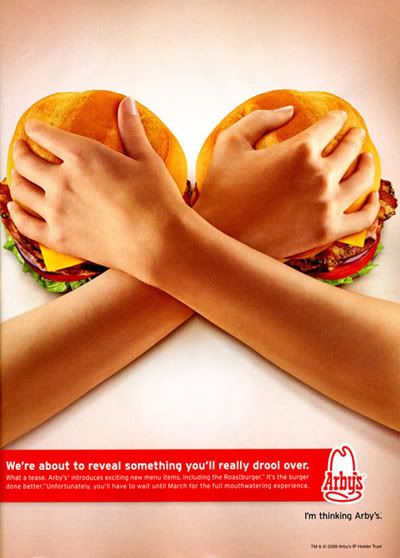

As briefly mentioned earlier, the marketing of meat has consistently excluded women from their target demographic. Because of this, meat campaigns appealing to men often include the sexualisation and objectification of both women and female farm animals.

Two examples of this include the way in which dairy products are packaged, and the way meat is advertised in commercials.

The packaging of most diary products show happy, free cows. Not only does this create a falsehood about the reality of dairy production, the female dairy animals are made to look like they want to be a part of their own exploitation, which can be interpreted as a reflection of the defence men use against sexual assault in humans; saying women are “asking for it”.

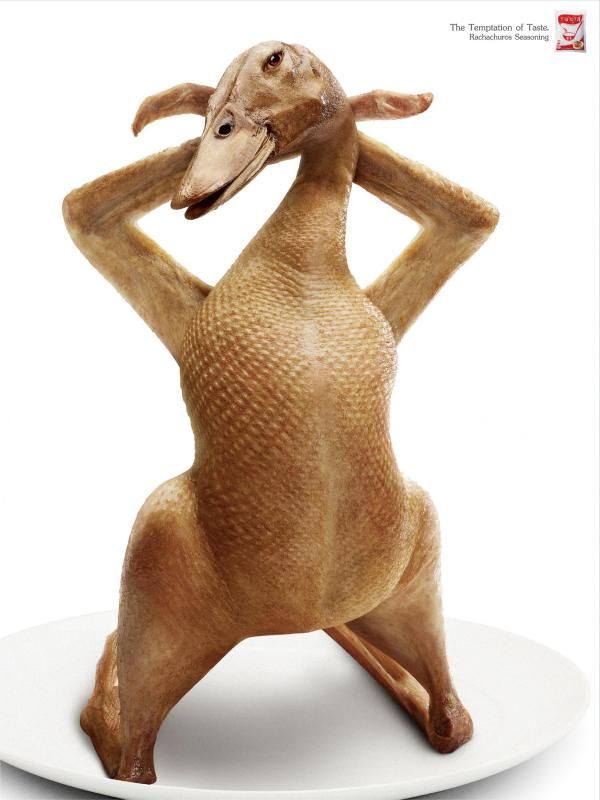

The commercial below created by Nando’s in South Africa blatantly showcases the objectification and sexualisation of women in the marketing of meat.

Similar to how women are “treated like a piece of meat” in real life, they are also represented this way in the marketing of meat. The woman in this commercial is reduced to her breasts, and is then compared to a chicken; worthless.

“A fragmented body becomes something to be used, but not something that has inherent worth.”

— Carol J. Adams

Women being reduced to their body parts is akin to how animals are renamed once they become meat. Once a living cow, now a plate of beef; once a living chicken, now a bucket of wings; once a living pig, now a rasher of bacon. It’s easy to disassociate a piece of meat with an animal if it’s being called something different — the same way in which women are seen as just “an ass” or “a pair of tits”. It’s dehumanising, harmful, and repressive.

Below are more examples showing the sexualisation of women in fast food print ads.

Fundamentally, the liberation of women and animals cannot be done without the other. In order to begin dismantling the patriarchy, women must acknowledge the misogyny that takes place in all parts of society; including our diet. And I believe it’s important to shed light on this particular issue as most people don’t recognise the connection between veganism and feminism, or the idea of anti-veganism feeding into sexism. Though I do think this is one of those issues where, once you see it, you can’t unsee it. I am especially interested in studying and bringing attention to this issue. And hopefully I can inspire others with this project.

Reference List:

Adams, C. J. (1990). ‘The sexual politics of meat: a feminist-vegetarian critical theory’, New York, Continuum.

Asher, K. Green, C. Dr Gutbrod, H. Jewell, M. Dr Hale, G. & Dr Bastian, B. (2014). Study of Current and Former Vegetarians and Vegans, Humane Research Council, <https://faunalytics.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Faunalytics_Current-Former-Vegetarians_Full-Report.pdf>

Ienatsch, Z. (2018). ‘Hatred of veganism is rooted in toxic masculinity’, The University Star, viewed 25 March 2021, <https://www.universitystar.com/opinions/hatred-of-veganism-is-rooted-in-toxic-masculinity/article_b1453b7a-63bf-51b6-8a04-4cc310803279.html>

Krantz, R. (2018). ‘6 ways the meat industry objectifies women’, The Lily, viewed 24 March 2021, <https://www.thelily.com/6-ways-the-meat-industry-objectifies-women/>

Radke, A. (2018). ‘Survey links sexism with meat eating’, Beef, Minneapolis.

Spechler, D. (2018). ‘Anti-Vegetarianism Is Sexism in Disguise’, Harper’s Bazaar, viewed 24 March 2021, <https://www.harpersbazaar.com/culture/politics/a14539150/anti-vegetarianism-sexism/>

Taylor, N. & Fraser, H. (2019). ‘Resisting sexism and speciesism in the social sciences: Using feminist, species‐inclusive, visual methods to value the work of women and (other) animals’, Gender, work, and organisation, vol. 26, no. 3, pp. 343–357.